Rudling’s Falsification of History: Case of the Holodomor

By Andrii Demchenko

Context

The Russian aggression against Ukraine has caused Holocaust researchers to fear becoming co-authors of the Russian concept of “denazification” of Ukraine in the eyes of the world community, which could harm their business. This was expressed extremely frankly and emotionally by Sergei Erlich, the editor of The Historical Expertise, during an interview with the Ukrainian historian Georgiy Kasianov in 2023:

Last year, i.e., before Putin’s invasion, I interviewed the Swedish scholar Per Rudling, who in particular studies the OUN/UPA, and the role of these organizations in the Holocaust. […] After Putin’s invasion, exposing the crimes of Ukraine’s ‘national heroes’ will be seen as working for the Kremlin. What should an honest historian do in this situation? Should he completely abandon stories related to Bandera, OUN-UPA, etc.?[i]

However, as the appearance of Rudling’s book[ii] demonstrates, the “honest historians” can feel at ease: exposing the “crimes of Ukraine’s ‘national heroes’” remains the content and purpose of the Holocaust study. As Rudling claims in the Introduction, “The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, its militias and paramilitaries need to be problematized, deconstructed, and scrutinized. As symbols for a liberal, democratic and pluralistic society they are tarnished heroes” (22). In his interview with Erlich, Rudling defined the content and goal of his professional activity as follows:

I am particularly interested in […] what a colleague refers to as the “Holodomor”– OUN-UPA narration of Ukrainian history. That is, a narration centered on the claim that the defining feature of modern Ukrainian history was a Muscovite-engineered genocide of the Ukrainian nation, in which at least seven, or ten million Ukrainians were exterminated in the Ukrainian SSR – and on a heroic narration of the OUN(b) and UPA’s heroic resistance fight against the “eternal enemies” of the Ukrainian people. I am particularly interested in the competitive victimisation narrative and the silence on the OUN and UPA’s involvement in the Holocaust and the 1943 Volhynian massacres.[iii]

As is well known, the Holocaust continues to be viewed as “the archetypal genocide – the “yardstick” by which one can measure and determine whether genocide has taken place.”[iv] It is therefore of great interest how the Holocaust scholars “measure” other genocides, particularly the Holodomor. The fact is that those who most loudly blame OUN and UPA are often those who most insistently downplay the significance of the Holodomor and distort its meaning. Rudling is just one of the most aggressive critics of OUN and UPA memory politics in Ukraine.

My comment is not a standard review. I will not analyze the structure and content of Rudling’s book in detail but focus on one issue related to Rudling’s “Holodomor – OUN-UPA” narration. I mean Rudling’s falsification of a document.

Rudling’s “ethnic group”

In Chapter 3, entitled Memory Management in Post-Soviet Ukraine, Rudling considers the use of a court “to police, manage, and control” the national memory of the Holodomor. Specifically, Rudling considers the ruling of the Kyiv City Court of Appeal dated 13 January 2010, concerning the crime of genocide in Ukraine in 1932-33. Stressing that the court “ruled the genocide aimed at exterminating Ukrainians, and, it underlined, not any other group” (106), Rudling quotes the ruling as follows:

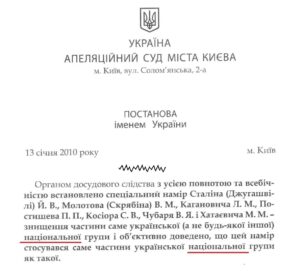

The criminal investigation body has fully and comprehensively established the special intention of Stalin, Molotov, Kaganovich, Postyshev, Kosior, Chubar and Khatayevych – to destroy a part specifically of the Ukrainian (and not any other) ethnic group and has objectively proved that this intention applied specifically to a part of the Ukrainian ethnic group as such.[v] (106)

Rudling refers to an English version of the ruling on an Internet resource. However, this version uses the incorrect term “ethnic group” instead of the correct “national group” (I have not investigated the reasons for the website error). This can be easily verified by comparing Rudling’s quote with a Ukrainian version on the same website or e.g. with an identical Ukrainian version on the website of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, so sharply criticized by Rudling, or e.g. with an identical Ukrainian version in an academic edition on the website of the Institute of History of Ukraine (Figure 1), which also contains a correct English version.

As is easily seen, the ruling does not contain the term “ethnic group” but only “national group”. In the rest three cases (105, 106), which are not considered here for the sake of brevity, Rudling also exploits the incorrect term “ethnic group.” In conclusion, Rudling notes with a hint of sarcasm: “Through this ruling, the court “settled” de jure a historical argument, that the famine constituted Holodomor[vi] – deliberate genocide, specifically and exclusively aimed at ethnic Ukrainians, and “not any other” ethnic group” (106). And immediately after that, he unexpectedly adds (Ibid.): “A week later, on 20 January 2010, Yushchenko, after having been defeated in the first round of the Ukrainian presidential elections, designated the late Stepan Bandera as Hero of Ukraine, posthumously awarding him the highest award of the Ukrainian state.” However, the fact is that genocide is, first of all, a legal concept. According to the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, it is for a competent tribunal to decide whether a specific crime constitutes genocide or not. Bandera’s unexpected appearance in the Holodomor topic will be discussed later.

Is Rudling’s mistake serious?

It is a rather serious mistake. The ruling is based on the 1948 UN Genocide Convention, which defines four different protected groups. The term “national group” is a legal one: it is impossible to confuse it with the term “ethnic group.” Ethnic Ukrainians lived in different parts of the USSR, but the Holodomor happened only to those who lived in Ukraine and Kuban and could (in reality and/or in the imagination of a perpetrator) realise their right to self-determination and an independent state. Of course, there is no isolated, pure group: the organisers of the Holodomor viewed Ukrainians as a social, ethnic and national group. However, they killed Ukrainians primarily as a national group. The ethnic (and social) characteristic only helped them to identify a target group – the Ukrainian national group. Therefore, Rudling’s mistake calls into question the definition of the Holodomor as a crime of genocide, since it distorts a material element of the crime. This mistake also distorts the historical context and reason for the genocide. Finally, it prevents the recognition of the Holodomor as genocide in the world and harms the memory of the victims.

Rudling’s concern about ethnicity

Rudling’s interest in ethnicity is not limited by the court ruling. In the same chapter, Rudling notes SBU’s list of the Holodomor organizers, especially paying attention to the ethnicity of the Jews involved in the crimes of the Holodomor:

In July 2008 the SBU published a list of 19 people “who provided the organizational-legal basis for the Holodomor-Genocide policies and repressions in Ukraine.” Eight of the individuals on the list were of Jewish background, and their ethnicity was underlined by the inclusion in parenthesis of their “real” Ashkenazi names alongside Slavic-sounding names. (104)

So what? Thankfully, Rudling explained what he meant in his 2019 work:

This action by the SBU was part of a larger campaign to mitigate the role of Western Ukrainian nationalists in the Holocaust (Kurylo and Himka 2008). Not only is it impossible to establish the ethnic origin of the people responsible for the famine, this sort of narrative also helps legitimize the extreme right’s conspiratorial interpretations of the famine as a Jewish and Russian genocide against the Ukrainian people, reinforcing anti-Semitic prejudice.[vii]

Rudling is wrong: the ethnic composition of the organizers of the Holodomor, at least in the organs of repression, is known. For example, Yurii Shapoval and Vadym Zolotaryov found that in 1932-33, “there were 75 people among senior personnel of GPU of the Ukrainian SSR, 50 (66.6%) of whom were Jewish by origin.”[viii] The eight Jews mentioned by Rudling constitute only 42% of the SBU list. Here it is appropriate to recall the national composition of Ukraine according to the census of 1926: Ukrainians – 80%, Russians – 9%, Jews – 5%. Finally, the SBU is a law enforcement agency and must reveal the real names of criminals, not hide them as Himka and Rudling believe.

In his 2019 work,[ix] Rudling writes that “the Holodomor discourse places a heavy emphasis put on ethnicity.” Then he notices: “The Holodomor discourse constitutes a particular interpretive and political framework, conceptualizing this event as a targeting a specific ethnic group, the Ukrainians.”[x] The Holocaust discourse also places a strong emphasis on ethnicity. So what?

Why is ethnicity so important for Rudling?

There are some reasons. First, the Holocaust is the dominant discourse in the West, and the Holodomor as a genocide of ethnic Ukrainians can threaten its status. As Claus Leggewie noted, “the classification of the Holodomor as a genocide has caused and continues to cause protests, especially among Jewish organizations because it […] relativizes the Holocaust and denies the uniqueness of the extermination of Jews.”[xi] Peter Novick explains: “In Jewish discourse on the Holocaust we have not just a competition for recognition but a competition for primacy. This takes many forms. Among the most widespread and pervasive is an angry insistence on the uniqueness of the Holocaust.”[xii] Novick quotes a chairman of the New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education who claimed that teaching of the victimhood of Poles and Ukrainians would “dilute and even deny the uniqueness of the Holocaust.”[xiii] Rudling also believes that the “systematic misuse” of the term “genocide” in Ukraine has “obfuscated the Holocaust” (342). It is strange: although Rudling often cites Eugene Finkel and Timothy Snyder, he does not mention that it was Finkel and Snyder, not Ukrainian nationalists, who first defined the crimes of Russians in Ukraine as genocide.

Second, the scholars who do not accept the genocidal theory of the Holodomor believe that the Holodomor was not specifically intended against ethnic Ukrainians. In particular, Hiroaki Kuromiya states: “Those who study the Great Famine from the perspective of the USSR as a whole tend to negate the specific Ukrainian factor: that the famine was in essence terror intended against ethnic Ukrainians, or a Ukrainian genocide. […] To support the Ukrainian genocide theory, one needs evidence that the Kremlin explicitly or implicitly discriminated against ethnic Ukrainians. […] True, the famine affected Ukraine severely; true, too, that Stalin distrusted the Ukrainian peasants and Ukrainian nationalists. Yet not enough evidence exists to show that Stalin engineered the famine to punish specifically the ethnic Ukrainians.”[xiv] I disagree with Kuromiya’s last statement, but I will not comment on it here.

Third, Ukraine, as a part of East Europe, is strongly associated with ethnic or “blood” nationalism in the West: “Not only the legacies of the German and Russian historical communities, but also the postwar political order have reinforced the marginalization of eastern and central Europe in North American academic politics. […] The history of the region became associated with nationalism, anti-Semitism and ethnic irredentism […]. By extension, the murderous legacy of national socialism and fascism, and their eastern and central European collaborators contributed to a demonization of nationalism as such… Good or “civic” nationalism is what the NATO countries enjoy, whereas eastern Europe (particularly the Balkans) and the third world generally are prone to bad or “ethnic” or “blood” nationalism. Clearly Ukraine, as a part of the eastern half of the European continent has been assigned to the “bad” category.”[xv]

Following this view, Rudling claims: “Notions of race clearly informed OUN(b) ethno-political violence during the war, both underlining the mass anti-Jewish pogroms in Western Ukraine in the summer of 1941 and their systematic massacres of the Polish minority in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia in 1943–44” (296). Apparently, ethnicity is not enough for Rudling because he devoted a separate chapter to racial and eugenic thought in the Ukrainian nationalist tradition (255). Despite his success, many questions remain open: in particular, it is not clear whether the Ukrainian nationalists used Jewish blood for ritual purposes.

Fourth, Rudling believes that the Holodomor cannot be considered separately from OUN and UPA – the Ukrainian nationalist organizations accused by Rudling of anti-Semitism, racism, ethnic cleansing, and participation in the Holocaust. Rudling’s approach to the Holodomor is not original: it is entirely based on the ideas of John-Paul Himka, whose Interventions Rudling cites (103). Although Rudling writes about two pillars of Ukrainian memory politics – “the Holodomor discourse” and “the cult of OUN and UPA” (Ibid.) – he views them following Himka as a single Ukrainian narration “OUN-UPA – Holodomor.” That is why Rudling unexpectedly mentioned Bandera in discussing the ruling (106). In his Interventions, Himka raised his now “classic” objections against the instrumentalization of the Holodomor with anti-Ukrainian undertones: “The genocide argument is used to buttress the campaign to glorify the anticommunist resistance of the Ukrainian nationalists during World War II. I do not think that Ukrainians who embrace the heritage of the wartime nationalists should be calling on the world to empathize with the victims of the famine if they are not able to empathize with the victims of the nationalists. I think, further, that there is something wrong with a campaign that finds its greatest resonance in the area of Ukraine where there was no famine, and in the overseas diaspora deriving from that region.”[xvi] In his 2019 work, Rudling quotes similar objections: “As John-Paul Himka (b. 1949) has noted,‘[t]he term (Holodomor – A.D.) is used primarily by those who consider the famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine to be genocide.’ Himka argues that the Ukrainian diaspora in North America ‘has its particular motive to position itself as victim: to refute perpetrator status. It tries to create an image of Ukrainians as a people to whom evil things were done, not the doer of evil. More to the point, it attempts to fashion a tale of victimization even larger than the Holocaust, the central event of World War II around which accusations against them have been formulated.’”[xvii] In his Erroneous methods,[xviii] Roman Serbyn raised arguments against Himka’s objections, not quoted by Rudling, in particular: i) the instrumentalization of a historical event does not change the nature of the event; ii) the recognition of a crime as genocide is contingent on objective criteria and not on the geographical distribution of its popular support.

So, why does Rudling need ethnicity? Apparently, ethnicity, in Rudling’s view, discredits Ukrainian memory politics. The point is that if Ukraine is strongly associated with ethnic or “blood” nationalism, and the Holodomor memory is closely related to that of OUN and UPA, as Rudling presupposes, and OUN and UPA are closely related to the ethnic cleansing, racism and anti-Semitism as Rudling claims, then the Ukrainian memory politics will be tarnished.

Is Rudling’s mistake accidental?

Quoting the court ruling, Rudling used the incorrect term “ethnic group” instead of the correct “national group.” The fact is that in other cases, he is very attentive to translation and transliteration: “nation” (natsiia) (99, 103, 281), “people” (narid) (103), “party doctrine” (partiinist’) (86, 125, 129, 130), etc. Rudling even corrects other writers when they make mistakes: e.g., Rudling corrected Taras Kuzio when Kuzio mistakenly translated Holodomory [Holodomors] as the Holodomor in singular: “The reference is to Holodomors, in plural […]” (342).

Rudling used an incorrect English version of the ruling but ignored a correct Ukrainian version on the same website. He also ignored both versions of a SBU Press Service’s report of January 13, 2010 (just the court hearing date) with the correct term “national group” on the same website. It is strange, but Rudling ignored the 2013[xix] and 2014[xx] academic editions with correct versions of the ruling on the website of the Institute of History of Ukraine. Rudling also ignored the well-known Entsyklopediia Holodomoru 1932 – 1933 rokiv v Ukraini[xxi] [Encyclopedia of Holodomor in 1932 – 1933 in Ukraine] of 2018 with a separate article devoted to the ruling on the website of the Institute. Therefore, sources containing the text of the ruling have existed since 2010. However, from all these sources, Rudling chose only one with the incorrect term. Is it possible that a meticulous scholar such as Rudling could have overlooked the others? It is unlikely. The point is that when he needs to humiliate OUN, he is even willing to look into the underpants of its leaders. Although this episode was not included in the chapter on eugenics, it remained in the previous version published as a single article.[xxii] In the article, Rudling claims that as a result of a wound received during the war, Yaroslav Stetsko suffered damage to his genitals and became a eunuch (I did not find confirmation of this fact in the literature cited by Rudling). It is therefore not surprising that the first thing the reader notices in Rudling’s book is not even its journalistic, far from academic style, but its selective character (the list of examples is too long to be presented in this note).

So, is Rudling’s mistake accidental? The fact is that Rudling knew that the court defined the national group as a target group of the Holodomor, not the ethnical one. In his 2013 work, Rudling notes: “Also the court system was assigned a role in the process; in the final days of Yushchenko’s presidency the Kyiv court of appeals posthumously found Stalin and the “leadership of the Bolshevik totalitarian regime guilty of genocide of the Ukrainian national group.”[xxiii] In his book, Rudling cites Kasianov’s Rozryta Mohyla (90, 98) and Memory Crash (336, 353), but ignores Kasianov’s remark: “On January 12, 2010, the Kyiv Court of Appeals started hearing a criminal case initiated by the Security Service of Ukraine “over the perpetration of genocide” by representatives of the supreme authorities of the Ukrainian SSR and the USSR against “a part of the Ukrainian national group.”[xxiv]

There is only one conclusion to be drawn from the above: This was not an accidental mistake. Rudling deliberately falsified the court ruling. Why? To discredit Ukraine’s memory politics. He was probably sure that in a country like Ukraine, where Bandera and Shukhevych are heroes, the court could only make such a decision. Rudling chose the incorrect term because he was sure that if he even falsified the ruling, nothing would happen to him, because the Holocaust is the dominant discourse in the West, and Ukraine is so weak that its opinion will be ignored.

Given the falsification, Rudling’s book cannot be seriously accepted as a reliable account of the historical figures and events he has set out to describe, but only as deliberate propaganda. A previous version of Rudling’s chapter containing the falsification was published as a single article in 2021 (81). In the article, Rudling thanks “Andreas Umland, who solicited constructive and very helpful comments from no less than five(!) anonymous reviewers.”[xxv] In the book, Rudling also thanks “Andreas Umland, whose enthusiastic encouragement played no small role for the appearance of this volume. From a Kyiv under Russian bombardment, Andreas solicited constructive and very helpful comments by multiple anonymous reviewers. Input and feedback by Julie Fedor and Yuliya Yurchuk have improved the text” (10). One can only express surprise that none of these experts noticed the falsification.

Andrii Demchenko

Independent Scholar

http://orcid.org/0009-0000-1803-1348

Notes

__________________________________

[i] Kasianov, 175.

[ii] Rudling, Tarnished Heroes.

[iii] Rudling, 19-20.

[iv] Gordon and O’Sullivan, Colonial Paradigms of Violence, 16.

[v] Rudling’s italics.

[vi] Rudling’s italics.

[vii] Rudling, “Anti-Semitism and the extreme right,” 220.

[viii] Shapoval and Zolotarov, “The Jews among senior personnel,” 52.

[ix] Rudling, “Terror Remembered, Terror Forgotten,” 416 – 417.

[x] Rudling’s italics.

[xi] Leggewie, Lang, Der Kampf um die europäische Erinnerung, 130.

[xii] Novick, The Holocaust in American Life, 23.

[xiii] Ibid., 218.

[xiv] Kuromiya, “The Soviet Famine of 1932–1933 Reconsidered,” 667, 673 – 674.

[xv] Von Hagen, “Does Ukraine Have a History?” 662.

[xvi] Himka, “Interventions,” 212.

[xvii] Rudling, “Terror Remembered, Terror Forgotten,” 416.

[xviii] Serbyn, “Erroneous Methods.”

[xix] Vasylenko, Antonovych, Holodomor 1932–1933 rokiv.

[xx] Gerasimenko, Udovichenko, Genocide in Ukraine in 1932–1933.

[xxi] Marochko, The Encyclopedia of Holodomor, 340.

[xxii] Rudling, “Eugenics and Racial Anthropology,” 81, 85.

[xxiii] Rudling, “Memories of ‘Holodomor’,” 242.

[xxiv] Kasianov, Rozryta Mohyla, 70; Memory Crash, 114. Emphasis added.

[xxv] Rudling, “Managing Memory,” 85. Rudling’s exclamation mark.

Bibliography

Gerasimenko M. and V. Udovichenko, eds. Henotsyd v Ukraini 1932–1933 rr. za materialamy kryminalnoi spravy № 475 [Genocide in Ukraine in 1932–1933 based on the materials of criminal case No. 475]. Kyiv, 2014. http://resource.history.org.ua/item/0009701

Gordon, Michelle and Rachel O’Sullivan. “Introduction: Colonial Paradigms of Violence.” In Colonial Paradigms of Violence. Comparative Analysis of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Mass Killing, edited by Michelle Gordon and Rachel O’Sullivan, Göttingen, 9 – 29. 2022.

Himka, John-Paul. “Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth Century Ukrainian History.” In The Convolutions of Historical Politics, edited by Alexei Miller and Maria Lipman, 211–238. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2012.

Kasianov, Georgiy. Memory Crash: The Politics of History in and around Ukraine 1980s–2010s. Budapest: Central

European University Press, 2022.

Kasianov, Georgiy. Rozryta mohyla: Holod 1932–1933 rokiv u politytsi, pam’iati ta istorii (1980-ti-2000-ni). Kharkiv: Folio, 2018.

Kasianov, Georgiy. “’There are people in Russia who protest, who receive fines and then jail terms.’ Interview with G. V. Kasianov.” Interview by Sergei Erlich. The Historical Expertise 34, no. 1 (2023):163–180. https://www.istorex.org/post/георгий-касьянов-в-россии-есть-люди-которые-протестуют-которые-получают-штрафы-а-потом-и-сроки

Kuromiya, Hiroaki. “The Soviet Famine of 1932–1933 Reconsidered,” Europe-Asia Studies 60, no. 4 (2008): 663-675.

Leggewie, Claus, and Anne Lang. Der Kampf um die europäische Erinnerung: Ein Schlachtfeld wird besichtigt. Munich: Beck, 2011.

Marochko, Vasyl, ed. Entsyklopediia Holodomoru 1932 – 1933 rokiv v Ukraini [Encyclopedia of Holodomor in 1932 – 1933 in Ukraine]. Drohobych: Kolo, 2018. http://resource.history.org.ua/item/0014295

Novick, Peter. The Holocaust in American Life. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999.

Rudling, Per Anders. “Anti-Semitism and the extreme right in contemporary Ukraine.” In Mapping the Extreme Right in Contemporary Europe From Local to Transnational, edited by Mammone A. et al., 189 – 205. Hoboken: Routledge, 2012.

Rudling, Per Anders. “Eugenics and Racial Anthropology in the Ukrainian Radical Nationalist Tradition” Science in Context, vol. 32, no. 1 (2019): 67-91.

Rudling, Per Anders. “’It is a sobering thought that ‘memory laws’ was originally a West European invention.’ Interview with Per Rudling. Interview with Per Rudling.” Interview by Sergei Erlich. The Historical Expertise 27 no.7 (2021):9–20. https://ac1e3a6f-914c-4de9-ab23-1dac1208aaf7.usrfiles.com/ugd/2fab34_e706503f64fe45b4822c25d2b3c8fd4b.pdf

Rudling, Per Anders. “Managing Memory in Post-Soviet Ukraine: From “Scientific Marxism-Leninism” to the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, 1991 – 2019.” Journal of Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society 7, no.2 (2021): 85–134.

Rudling, Per Anders. “Memories of ‘Holodomor’ and National Socialism in Ukrainian Political Culture.” In Rekonstruktion des Nationalmythos?: Frankreich, Deutschland und die Ukraine im Vergleich, edited by Yves Bizeul, 227–258. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2013.

Rudling, Per Anders. Tarnished Heroes: The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in the Memory Politics of Post-Soviet Ukraine. Stuttgart: Ibidem Press, 2024.

Rudling, Per Anders. “Terror Remembered, Terror Forgotten: Stalinist, Nazi, and Nationalist Atrocities in Ukrainian ‘National Memory.” In World War II Re-explored: Some New Millennium Studies in the History of the Global Confict, edited by Suchoples, J. et al., 401 – 428. Berlin: Peter Lang, 2019.

Serbyn, Roman. “Erroneous Methods in J.-P. Himka’s Challenge to “Ukrainian Myths.” Current Politics in Ukraine. Opinion and analysis on current events in Ukraine, August 7, 2011. https://ukraineanalysis.wordpress.com/2011/08/07/erroneous-methods-in-j-p-himka%E2%80%99s-challenge-to-%E2%80%9Cukrainian-myths%E2%80%9D/

Shapoval, Yu. and V. Zolotaryov. “The Jews among senior personnel of GPU–NKVD of the UkSSR during 1920th–30th.” From the archives of the VUChK, GPU, NKVD, KGB 34, no.1 (2010):53–93. http://resource.history.org.ua/publ/gpu_2010_1_53

Vasylenko, Volodymyr, and Myroslava Antonovych, eds. Holodomor 1932–1933 rokiv v Ukraini iak zlochyn henotsydu zhidno z mizhnarodnym pravom [The Holodomor of 1932–1933 in Ukraine as a Crime of Genocide under International Law] (in English and Ukrainian). Kyiv: Vydavnychyi dim “Kyievo-Mohylianska akademia,” 2013, http://resource.history.org.ua/item/0010125

Von Hagen, Mark. “Does Ukraine Have a History?” Slavic Review , 54 no. 3 (1995): 658-673.

__________________________________

THE PARLIAMENT OF ICELAND RECOGNIZED THE HOLODOMOR AS A GENOCIDE OF UKRAINIANS

YEVROPEYSKA PRAVDA

MARCH 23, 2023

The Parliament of Iceland on Thursday voted for a resolution recognizing the Holodomor of 1932-1933 as genocide of the Ukrainian people.

This is reported by “Yevropeyska Pravda” with reference to mbl.is.

The resolution was unanimously supported by all 48 deputies who were present at the meeting, and these were deputies from all parties represented in the parliament.

Having approved the proposal in the parliament today, Iceland joins the group of countries that responded to Ukraine’s call and declared the Holodomor a genocide of Ukrainians. Other countries that have done the same include the United States, Germany, Ireland and Canada.President Volodymyr Zelenskyy thanked Iceland for the adopted resolution. “I am grateful to Iceland for recognizing the Holodomor of 1932-1933 as genocide of the Ukrainian people, for honoring the memory of millions of Ukrainians killed by the Moscow regime. This is a clear signal that such crimes do not go unpunished and do not have a statute of limitations,” he wrote on Twitter.

We will remind you that on March 10, the House of Representatives of Belgium, the lower house of the Belgian parliament, recognized the Holodomor as genocide of the Ukrainian people.On December 15, the European Parliament recognized the Holodomor as genocide.